There were many different type Flares. These are the Flares dropped from our Hueys at night in Vietnam.

Stan Allen Nighthawk - Tom Fleming Stable Boy - Tom Dooling Cobra Night Attacks - VHPA Pilot Stories - Images

NightHawk Missions (Stan Allen Crew Chief 1969-70): In my memory, we used flares a lot on the Night Hawk missions. At first, we tried to coordinate the use of artillery flares with our missions. That was a complete failure because we did not have direct control over the flares to place them exactly when and where we needed them. You never knew exactly when or where they would pop. In addition, there was the danger of us being in the line of fire from the artillery. They did not burn long enough for us to get into position to use them to any advantage. They also lit us up so it made us a target.

NightHawk Missions (Stan Allen Crew Chief 1969-70): In my memory, we used flares a lot on the Night Hawk missions. At first, we tried to coordinate the use of artillery flares with our missions. That was a complete failure because we did not have direct control over the flares to place them exactly when and where we needed them. You never knew exactly when or where they would pop. In addition, there was the danger of us being in the line of fire from the artillery. They did not burn long enough for us to get into position to use them to any advantage. They also lit us up so it made us a target.

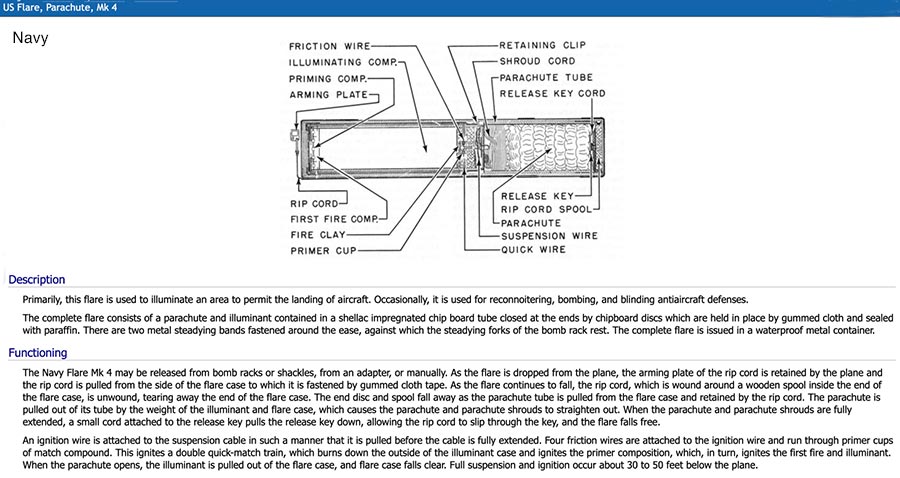

We started using US Navy flares. I do not know how we got access to them but we could get them from the re-arm point at Cu Chi. As I remember them, they were a bright aluminum tube approximately 3 feet long and probably 4 or 5 inches in diameter, relatively heavy, with a lanyard 6 to 8 feet long, attached to one end. We installed a D-ring to one of the cargo tie down points on the floor of the UH-1 that we were using for the Night Hawk bird. You then would attach the loop in the end of the lanyard to the D-ring and toss the flare out the door when and where you needed it. When it hit the end of the lanyard, it would activate. We then circled above the parachute, staying in the shadow it created to hide. Theoretically, this made it impossible for the enemy to see us as they had to look up through the brightness of the flare to try to see us flying blackout above the parachute in the cone of darkness above it. It was a theory that worked, ( I guess,) as I have never been on the ground looking up to see if it is, in fact, true that we could not be seen. These flares were very bright. They would burn for somewhere in the neighborhood of 3 to 5 minutes. I never timed one but I do know that they burned much longer than the artillery flares did. When we were circling above the flare, we could not be seen but they would light up about half of whatever Provence you were operating in. It gave us a better picture of the situation as a whole of the area, much more than just what we could see in the beam of the Xenon Arc light that we used most of the time. We used flares when we knew or suspected that there was more activity in the area than we had discovered using the Xenon Arc light. We would fly to the approximate center of the area that we suspected was active and then throw out a flare and see what we could see.

With the bright light from the Navy flares, we could see almost as well as you could in bright sunlight making it easy to see and identify your target and eliminate it.

I do not remember any formal training for this action; we just threw out one and ad-libbed from there. The only training that I can remember for someone new to Night Hawk was that they were shown how to hook the lanyard to the D-ring before throwing the flare out the door keeping your hands and feet free of the lanyard as you threw. If you did not, the flare might drag you out with it. Only throw a flare when instructed by the Aircraft Commander.

The flares were loaded into a fiberglass tub that was strapped to the floor and the transmission wall in the cargo area for the UH-1. I do not know what the tub was originally designed for, but it was definitely military hardware. It had an aluminum frame with fiberglass walls, with one wall on one side that was sloped outward. It was OD green, as I recall, it would hold somewhere around 12 to 15 flares, stacked like cord wood in the tub. The flares were not secured in the tub; they just laid there until you needed them.

Stable Boy Flys Flare Missions (Tom Fleming Maintenance Officer 1967):

In 1967 we started using the 3 million candle power flares. I don't know if they had been used prior to my arrival. I was serving as Stable Boy Aircraft Commander at that time. I had used them in a prior assignment in Korea in 1962 from an L 20 Beaver (fixed wing) and knew of their effectiveness. These flares may have been a different model of the Navy ones mentioned in the Stan Allen article. I think they were the USAF variety.

The flares we used were fused to go off upon a settable number of seconds after they were dropped. The normal drop altitudes for optimum delivery was 3000 ft. This gave a 500 ft burn out and optimum illumination coverage. Could be dropped higher if you had to fly on top of a cloud layer, if you set the timer. The flares were stacked in the floor, attached to the UH 1D floor rings as described, and pitched out by the Crew Chief or Door Gunner. I trained the crew on the first use and there had been no prior training.

Our first use was to illuminate the path for CPT Strickland's Armored Cav troop as the dashed up through the Filhol Rubber Plantation to rescue a company of Manchu 9th Infantry Division who had been over run by the VC at an ARVN Base Camp up on the Saigon river.

I had 54 flares loaded in Stable boy (over weight) after that we reduced the number so we could hover. After that initial use the Centaurs were called on to preplanned Cordon and Seizure missions by the Squadron, as well as on call missions.

In the fall of 1967 the Squadron was tasked to conduct night convoy runs from Chu Chi to Tay Ninh as well as nightly air assault landings astride the Main Supply Route. None of these missions had been previously preformed. The Squadron was given one week to prepare. We worked out a procedure where the C&C Aircraft would circle about 2-3 Klicks to the left rear of the LZ and commence dropping flares to provide moon light strength illumination for the Aero Rifle lift ships as they called SP Inbound. This gave the Aircraft Commanders enough illumination to see the LZ and the Aero Rifles to see the areas as they deployed with out being illuminated.

We practiced and adjusted that first week without the rifle men to iron out the procedures. It worked well. We also experimented with a tank xeon searchlight mounted on the firewall of a UH-1C that had been a Hog and was no longer capable of mounting a 40 mm grenade launcher. The crew used a starlight scope when illumination was infrared. Unfortunately the project didn't work out and was abandoned.

Flares Supporting Cobra Night Attack Missions (Tom Dooling Cobra Pilot): As Stan says, they were great for turning the night into day, but my most vivid memory was that we would be making diving rocket runs under flare illumination where we would pull out around 500 feet, and occasionally, there would be a burned-out flare hanging from its parachute that we couldn’t see until we were pretty close to it - really raised the pucker factor coming out of a gun run and seeing a parachute right off your wing, sometimes only 30-40 meters away!! The other story about flares I remember, was that (I think it was a Little Bear, but it could have been one of the Centaurs) a flare ship had a flare ignite in the cargo compartment - and one of the crew members heroically grabbed it and threw it out, and was burned pretty badly. Talk about pucker factor!!

Stories from other unit pilots:

....Leslie Smith (Unit unknown).

The flares were a 24 lbs piece of magnesium attached to a 21’ parachute, the whole thing was housed in an aluminum tube about 4” x 5’. The ones I saw were always dropped out of helicopters but you could do it from airplanes too. They were attached to the dropping aircraft with a rip cord, when the flare reached the end of the cord it would break free and start a reaction. A small charge would push the flare and parachute out of the aluminum tube they were stored in. As the flare and chute came out the parachute deployed and the flare ignited. The flare would light up a grid square (1,000,000 square meters) and burn for about a minute or so.

I flew DustOff, on night missions they were used regularly. The flares where also a hazard to helicopters that we had to really watch out for, as I mentioned their chute was 21’. Once the flare went out the chute was still inflated but virtually invisible. If you flew into one it would take you out of the air and kill everyone onboard. To guard against this we would put the flare ship on the down wind side of the area we were flying in, this way they drifted away from us. On a single mission it was not uncommon to use up to a dozen or more. You also had to plan your approach so as to have light continuously until we were on the ground. If the light went out on short final you were up the proverbial creek, you can’t even begin to understand how dark rural Vietnam was. You tried not to use your own landing lights, they made you a very inviting and visible target. Typically we used our lights only for the last 10’ or so, once you were on the ground the light went out. In fact we would conduct these night missions in as dark a mode as possible, no anti-collision lights, no position lights, no internal lights, and we would turn our instrument lights to red and dim them so much that we could barely see them.

.....CW4 Mike Jones B Troop Blues 7/17th Air Cav, Jan 1968-Jan 1969 (VHPA Story)

Of all the crazy flying we did flying flare missions had its own unique ways of dying. And they make for bad dreams if you happen to survive a flare accident.

Most of the attacks on our bases occurred at night. The Army’s solution- turn the night into day by dropping very bright magnesium parachute flares from helicopters over the camp’s perimeter. The MK-24 parachute flare was in wide use for this purpose. It puts out over 2- million candlepower for about 3 minutes as it descends under a 16-foot diameter parachute. It burned at 5000oF and could illuminate a large area bright enough to read by. When a camp came under attack, quick reaction aircrews scrambled into the air, usually a couple of gunships and a UH-1D or H flare ship. The MK-24 flare is housed in an aluminum canister about 36- inches long and 4 1/2-inches in diameter weighing about 30-pounds. Located at the top of the canister are two setting knobs, the first a delay timer setting the time in seconds that the flare will fall to clear the aircraft and deploy the parachute at the right altitude to give maximum illumination over the target area. This timer is triggered when a steel lanyard with its end clipped to a short static line attached to the helicopter. When the flare is tossed out by the crew chief it falls to the end of the static line initiating a jerk that starts the timer. It only takes a 12- pound pull to initiate the flare. The lanyard breaks away from the helicopter and the falling flare counts off the number of seconds of freefall before the parachute deploys. The second timer knob determines the number of seconds from initial lanyard pull to flare ignition. The flare now descends under parachute, burning white hot for three minutes, The aircrew must determine these timer values before takeoff and replace a plastic protective cover over the setting knobs and coiled up lanyard to prevent accidentally pulling on a dangling lanyard. As many as 60 flares were stacked on the cabin floor just ahead of where the door gunner and crew chief sat. The pilot would do a quick engine start and be airborne in 5 minutes from initial call to launch. The helicopter would quickly climb to drop altitude, usually around 3,000 feet above the camp.

2 MK-24 parachute flares over our Phan Thiet camp. Red tracer rounds are from our AH-1G Cobra gunships. Aug 1968

Below the gunships were getting into position to make runs along the perimeter. The flare ship pilot would set up his run upwind of the drop area and tell the guys in back to get ready to drop. The door gunner, sitting on the right side of the cabin would pick up a flare and place it in his lap and remove the plastic safety cap. He then handed it to the crew chief sitting on the left side. The flare lanyard was snapped to the helicopter’s static line. On command the crew chief would toss the flare out. In our case the right cargo door was sometimes closed. The

mission would continue as corrections were made to

altitude, and drop points for optimum and overlapping illumination coverage.

It was a surreal scene viewed from above as the Cobra’s worked under the flare light. Done right we could keep constant illumination over the camp with overlapping flares. We could keep this up for a complete fuel load, more than 2 hours.

On this particular July night in 1968 my crew was on 5-minute alert at Phan Thiet airfield. B Troop’s camp was a hastily built site about a mile south of the airfield just outside Phan Thiet’s perimeter. The call came to me late in the evening to scramble, the camp was under attack! 5 minutes later we were airborne and climbing to altitude. Off to the south we could see our guard towers’ 50 cal machine guns raking the southern perimeter fences. Trip flares had been set off by a 16-man enemy sapper team. They had been caught in the open. We began chucking flares out at 3,000 feet and soon the whole area was lit up. All the sudden there was a loud explosion and bright flash in the back of our Huey. A flare had ejected inside the cabin. We had 10 seconds before the flare ignited. I began an emergency descent. We had only dropped a few flares. 10 seconds passed and we were still alive, but where was the flare? I turned around to see what was going on behind me. The door gunner was doubled over and bleeding! He had just handed a flare to the crew chief when the flare and parachute ejected from its aluminum tube. He had inadvertently pulled the arming lanyard while removing the plastic safety cap before handing it to the crew chief. The flare exited out the left side of the helicopter. The outer tube fired back across the cabin striking the door gunner in the kneecap, continued to the right striking the closed cargo door and bounced back out the left side of the helicopter. The flare and parachute didn’t hang up on the skid or other parts of the airframe.

We lucked out that the parachute didn’t end up in the tail rotor. The crew chief lost his left kneecap. We were finished for the night. There were tales of others who weren’t so lucky when flares had ignited inside the helicopter.

Images relating to dropping flares: